Recent developments in nonreciprocal thermal radiation, including findings from Penn State University (PSU), have garnered significant attention from the scientific community. The outcomes of their studies are interpreted as an infringement of the 165-year-old Kirchhoff’s law of thermal radiation. In PSU’s study, enhanced emissivity was observed from a 2.2μm-thick metamaterial microfilm composed of five successive 0.44μ m-thick electron-doped InGaAs (indium gallium arsenide) layers atop a 0.10μm gold (Au) layer with an augmented doping gradient along the thickness. This layered structure was thermally bonded to a silicon (Si) substrate, and radiation attributes were investigated at temperatures of 294 K and 540 K. The study reported a nonreciprocal thermal emission (Δε = 0.43) under a magnetic field of 5.0 Tatλ = 21.6 μm and an angle θ = 55∘. This outcome of nonreciprocal thermal emission is promising for applications such as infrared camouflage, thermal cloaking, and energy conversion. However, the underlying physical mechanisms responsible for this nonreciprocal behavior, particularly the role of electro-thermo-magnetic effects in the metamaterial microstructure, were not addressed in their study. In addition, nonreciprocal emissivity was not observed in several similar studies that did not apply a magnetic field to the metamaterial. This study aims to explore the underlying mechanisms behind nonreciprocal thermal radiation from a metamaterial under magnetic fields, thereby strengthening recent findings, including those from PSU, which preserve consistency with the first law of thermodynamics, and deepen the understanding of Kirchhoff’s law. Exploring the underlying mechanism of the research is vital for scientists and boosts the reader’s perspective. Additionally, it will aid in designing advanced metamaterials for emerging technologies, including thermal diodes, radiative heat engines, energy harvesting, thermal management, and MEMS sensing.

Kirchhoff’s law is a crucial aspect of thermal radiation, which states that the emissivity \((e)\) and absorptivity \((\alpha)\) of radiation from an isothermal body are equal for a definite frequency, direction, and polarization [1], a statement that is validated by several praiseworthy studies [2– 5]. If the emissivity \((e)\) and absorptivity \((\alpha)\) of radiation from an isothermal body are not equal in a given direction and wavelength, then the body exhibits nonreciprocal emissivity. Kattawar and Eisner [2] validated Kirchhoff’s law for a homogeneous isothermal sphere. Luo et al. [3] proved that the emission \((e)\) from a uniform photonic crystal slab is equal to its absorbance \((\alpha)\) for a specified polarization angle and frequency of thermal radiation. Wang et al. [4] revealed that the emissivity \((e)\) and absorption \((\alpha)\) of radiation from structured layers (Au thin film, SiO\(_2\) cavity, opaque Au film, and Si wafer) numerically agree with Kirchhoff’s law of radiation. In addition, Chan et al. [5] explored that Kirchhoff’s law holds for the emission \((e)\) and absorption \((\alpha)\) spectra from a 3D periodic photonic crystal slab. In those studies, the outcomes agreed with Kirchhoff’s law, where the experimental bodies or metamaterials were not subjected to an external source or field, such as magnetic fields or electric fields. However, recent studies [6– 9] reported higher emissivity \((e)\) than absorptivity \((\alpha)\) from a body under the influence of a magnetic field or external agitation, which suggests the emergence of nonreciprocal thermal radiation phenomena. This suggests that Kirchhoff’s law may not hold in non-equilibrium conditions or when external fields are applied, warranting further investigation into the underlying mechanisms responsible for these deviations.

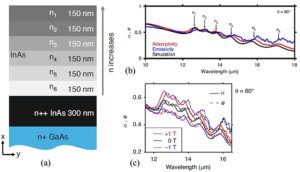

In the study of Shayegan et al. [6], one-tesla (T) transverse magnetic field was applied to a single-layer indium arsenide (InAs) structure, which stimulates cyclotron motion of electrons in the microstructure, and a notable contrast of 0.22 was observed between the emissivity \((e)\) and absorptivity \((\alpha)\), as depicted in Figure 2(e) of their study [6]. It is interpreted as an infringement of Kirchhoff’s law of thermal radiation [10]. Part et al. [7] numerically predicted a substantial difference between emissivity \((e)\) and absorptivity \((\alpha)\) in a photonic crystal slab made of a magnetic Weyl semimetal and silicon. Yet, this outcome is primarily predicted based on the theory and still awaits experimental verification [10]. In the further study of Shayegan et al., the contrast of 0.12 (approx.) was reported between emissivity \((e)\) and absorptivity \((\alpha)\) (as per [9]) from a graded ENZ (Epsilon-Near-Zero) metamaterial microstructure of subwavelength InAs layers under a magnetic field of 1.0 T within wavelength \(\lambda = 16\)–\(18~\mu\text{m}\), as shown in Figure 1(b) [8]. They reported that nonreciprocity varies with microstructure sub-wavelength thickness and the order of carrier concentration gradient, increasing within six layers (0.15 \(\mu\) m each) from top to bottom, as shown in Figure 1(a). The intensity of nonreciprocity was found to be negligible in the absence of a magnetic field (0 T), whereas a significant nonreciprocity was reported under the magnetic fields of \(1.0\) T and \(-1.0\) T, as shown in Figure 1-c [8]. It is also interpreted as the unlocking of Kirchhoff’s law of radiation.

In the PSU’s study [9], a high emissivity was achieved from a \(2.2~\mu\text{m}\) thick epsilon-near-zero (ENZ) metamaterial microfilm under an external magnetic field of \(5.0\) T. The microfilm was engineered with five successive \(0.44~\mu\text{m}\)-thick layers of electron-doped indium gallium arsenide (InGaAs) deposited over a \(0.10~\mu\text{m}\) gold (Au) layer. The doping concentration was increased along the thickness of the layers, consistent with the study of Shayegan et al. [8]. The multilayer microstructure was then thermally bonded to a silicon (Si) substrate, allowing for nonreciprocal applications. InGaAs exhibits a diverse range of crystal lattice structures and is widely employed in optoelectronics, high-speed electronics, photonics, and short-wave infrared (SWIR) technologies. In their study, nonreciprocity \((\Delta e)\), defined as the difference between emissivity \((e)\) and absorptivity \((\alpha)\), was evaluated under opposing magnetic fields of \(5\) T and \(-5\) T, equivalent to \(\Delta e = e(5~\mathrm{T}) – \alpha(5~\mathrm{T})\). The maximum nonreciprocity of \(\Delta e = 0.43\) was noticed at \(\lambda = 21.6~\mu\text{m}\) and \(\theta = 55^\circ\) under a \(5.0\) T magnetic field.

This remarkable outcome reveals strong potential for practical applications in infrared camouflage and cloaking devices, thermal diodes, radiative heat engines, nonreciprocal thermal photonics for thermal management and energy harvesting, as well as MEMS sensing, is evident. However, the underlying mechanism for generating nonreciprocal thermal emission \((\Delta e)\) from a specially designed microstructure under a magnetic field was not addressed in the PSU study, which is crucial for advancing the understanding of nonreciprocal thermal emission. Therefore, the present study aims to explore the underlying factors governing nonreciprocal thermal radiation \((\Delta e)\) in the specially designed metamaterial microstructure. It will enrich the outcome of the study by Zhang et al. [9] and also deepen the understanding of 165-year-old Kirchhoff’s law of thermal radiation.

Kirchhoff’s law of radiation is upheld in the studies [2– 5], where the emissivity \((e)\) and absorptivity \((\alpha)\) from a body are evaluated in the absence of an external magnetic field. In contrast, the nonreciprocal thermal radiation \((\Delta e)\) is observed in the studies [6– 9], where specially designed and fabricated single- or multilayers of InAs, photonic crystal microslab, and InGaAs microstructures were employed on a micrometer (\(10^{-6}\) m) scale and subjected to magnetic fields ranging from \(1.0\) T to \(5.0\) T. In this study, the underlying mechanisms of the evolution of nonreciprocal thermal radiation \((\Delta e)\) in specially engineered metamaterials under an external magnetic field are investigated through the lens of electro-thermo-magnetic interactions in the microstructure. This approach is justified since prior studies were conducted on metamaterial structures whose dimensions fall within the typical range of microstructures (1–100 \(\mu\) m) [11].

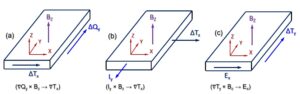

Due to the micro-scale dimensions, the influence of external electro-thermo-magnetic fields on the mechanical and electrical behavior of microstructures becomes significantly more pronounced compared to bulk materials [12]. The primary electro-thermo-magnetic phenomena relevant in this context are the Righi–Leduc, Ettingshausen, and Nernst effects [13]. These effects occur when any two of the three fields—electric field (\(E\)), magnetic field (\(B\)), and thermal gradient (VT)—are applied orthogonally within the same plane of a microstructure, resulting in the emergence of a third induced field or force in the perpendicular direction [13], as illustrated in Figure 2. These effects are particularly dominant in micro-scale materials that are inhomogeneous, composed of dissimilar constituents, or exhibit a gradient in carrier density [13, 14].

In this study, the underlying mechanism responsible for the emergence of nonreciprocity \((\Delta e)\) in metamaterials under the influence of an external magnetic field is investigated and interpreted through the lens of three key electro-thermo-magnetic effects, supported by relevant literature.

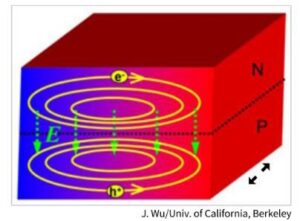

Due to the Righi–Leduc effect, a transverse temperature gradient \((\mathrm{VT}_x)\) is induced within a microstructure when it is subjected to a longitudinal heat flow \((\mathrm{VQ}_y)\) and simultaneously exposed to a magnetic field \((B_z)\), as shown in Figure 2(a). Similarly, the Ettingshausen effect results in the formation of a transverse temperature gradient \((\mathrm{VT}_z)\) when an electric current \((I_y)\) flows through the microstructure in the presence of a magnetic field \((B_z)\), as shown in Figure 2(b). Similarly, a transverse electric field \((E_x)\) is generated within a microstructure due to the Nernst effect if it experiences a thermal gradient \((\mathrm{VT}_y)\) and a magnetic field \((B_z)\) simultaneously in the two perpendicular planes, as depicted in Figure 2(c). Furthermore, according to S. R. Das [15], the existence of a temperature gradient—or localized hot and cold regions—within a semiconductor or microstructure can induce circulating currents and associated magnetic fields. Notably, when an n-type semiconductor is placed over a p-type semiconductor and subjected to both a circulating current vortex and a magnetic field, a temperature gradient is generated across the semiconductors, as illustrated in Figure 3. This finding aligns with the electro-thermo-magnetic effects on semiconductor or metamaterial microstructures.

In the study of Shayegan et al. [6], the maximum nonreciprocity \((\Delta e)\) was found to be \(0.22\) (at \(\lambda = 12.65~\mu\text{m}\) and \(\theta = 65^\circ\)) under an in–plane magnetic field of \(1.0\) T from a GMR (guided–mode resonance) structure coupled to photonic \(n\)-InAs. The GMR structure (a-Si: amorphous silicon) was placed on top of \(n\)-InAs. The slab and groove depth and the grating periodicity (\(\Lambda\)) of the GMR structure were \(0.50~\mu\text{m}\), \(1.55~\mu\text{m}\), and \(5.50~\mu\text{m}\), respectively, to ensure that the \(+1\)st-order TM (transverse–magnetic) mode aligns with the ENZ (epsilon–near–zero) wavelength of \(n\)-InAs over a wide range of angles when the grating is aligned at \(\phi = 0^\circ\) [6]. The outcome of their study was declared an infringement of Kirchhoff’s law of thermal radiation [6]. Although the nonreciprocity \((\Delta e)\) of radiation was not observed in their study in the absence of a magnetic field (see Figure 2(h) in [6]), indium arsenide (\(n\)-type InAs) develops free carriers (electrons), exhibits ENZ redshift, generates electron–hole pairs, and increases electrical conductivity when subjected to light or thermal load. Consequently, under an applied magnetic field, additional emissivity is developed in the GMR due to the Ettingshausen effect, as shown in Figure 2(b). This occurs since the carrier gradient within the metamaterial causes electron flow.

In their subsequent study [8], the magnitude of nonreciprocity \((\Delta e)\) was also observed to be zero at \(0\) T magnetic field for wavelengths between \(\lambda = 12.5\) to \(15~\mu\text{m}\) from InAs layers of subwavelength thicknesses \(0.05~\mu\text{m}\) and \(0.15~\mu\text{m}\) in [8]). In contrast, \(\Delta e \approx 0.12\) was measured under a \(1.0\) T magnetic field. In addition, the difference between emissivity \((e)\) and absorptivity \((\alpha)\) was found to be almost negligible at zero magnetic field, as shown in Figure 1(c). The negligible amount of nonreciprocity \((\Delta e)\) at zero magnetic field is attributed to electro–thermo–magnetic effects arising from the existence of a carrier gradient across the depth of InAs layers. It indicates without applying an external field or energy, such as a magnetic field, the nonreciprocity of thermal radiation can’t be achieved.

Investigation of PSU by Zhang et al. [9] reveals that the maximum nonreciprocity \((\Delta e)\) is \(0.43\) obtained from a \(0.44~\mu\text{m}\) thick InGaAs microfilm under a magnetic field of \(5.0\) T at \(\lambda = 21.6~\mu\text{m}\) and \(\theta = 55^\circ\). However, at \(55^\circ\) TM (transverse magnetic) polarization, the magnitude of \(\Delta e\) was observed to be zero for all wavelengths at zero magnetic field (Figure 3(c) of [9]). Negligible nonreciprocal emissivity \((e \approx 0.1)\) is also observed at a \(55^\circ\) angle TE (transverse electric) polarization at \(\lambda = 21.6~\mu\text{m}\) under zero magnetic field (Figure 3(f) of [9]). This behavior is attributed to the development of a temperature gradient (Figure 3) across the specimen, since it is made of three different layers of materials (InGaAs) and the doping density varies along the depth. The variation in thermal conductivity, thermal inertia, and charge carrier mobility within the three different layer materials also leads to the development of a temperature gradient in the specimen and an insignificant nonreciprocal emissivity \((e \approx 0.1)\).

In all those studies [6, 8, 9], the magnitude of nonreciprocity \((\Delta e)\) is only observed in the presence of external agitation or magnetic fields or energy, which is raised due to the electro-thermo-magnetic effects such as the Righi–Leduc, Ettingshausen, and Nernst effects (Figure 2). For the same reason, and due to the presence of a doping density gradient in the specimen, the emissivity \((e)\) is found to be stronger along positive angles for the \(5.0\) T magnetic field and negative angles for the \(-5.0\) T magnetic field. In those experimental studies [6, 8, 9], it is revealed that the magnitude of emissivity \((e)\) and nonreciprocity \((\Delta e)\) increase almost linearly with the intensity of external agitation or magnetic field. Without an external source, field, energy, or agitation across the metamaterial, nonreciprocity cannot be achieved.

The praiseworthy outcomes of nonreciprocal thermal radiation research, including that conducted by Penn State University (PSU), hold promise for applications in infrared camouflage and cloaking devices, energy harvesting and conversion, thermal diodes, radiative heat engines, nonreciprocal thermal photonics for thermal management, and MEMS sensing. However, the underlying mechanism of receiving nonreciprocal thermal emission from a specially designed metamaterial under a magnetic field is not addressed in their study. By investigating relevant experimental studies, it is evident that the magnitude of nonreciprocal emissivity increases with the strength of external magnetic fields and is only achieved in the presence of a magnetic field, which signifies that this effect is inherently linked to external energy inputs. This nonreciprocal behavior of thermal radiation can be ascribed to electro-thermo-magnetic phenomena, such as the Righi-Leduc, Ettingshausen, and Nernst effects, which played a role in the microstructural metamaterials employed in the study. Although a numerical study suggests that nonreciprocal thermal emission could be theoretically achieved without an external magnetic field, using photonic crystal slabs composed of magnetic Weyl semimetals and silicon, the experimental validation of such a claim still remains pending. Kirchhoff’s law of radiation remains valid under ideal conditions, where no external agitation or energy is employed. The presence of an external energy source, such as a magnetic field, is crucial to observe deviations from this classical law, thereby preserving consistency with the first law of thermodynamics. This study highlights the importance of exploring the electro-thermo-magnetic origins of nonreciprocal thermal radiation, offering a foundational understanding for enhancing such effects in future applications. It is crucial to support and expand PSU’s pioneering outcomes, deepen the understanding of fundamental principles, and deepen the perception of Kirchhoff’s law of thermal radiation, established over 165 years ago.

The author declares no conflict of interests.

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the author upon reasonable request.

Greffet, J.J., Bouchon, P., Brucoli, G., Sakat, E., & Marquier, F. (2016). Generalized Kirchhoff law. arXiv preprint arXiv:1601.00312.

Kattawar, G.W., & Eisner, M., (1970). Radiation from a Homogeneous Isothermal Sphere. Applied Optics, 9(12), 2685–2690.

Luo, C., Narayanaswamy, A., Chen, G., & Joannopoulos, J. D. (2004). Thermal radiation from photonic crystals: A direct calculation. Physical Review Letters, 93(21), 213905.

Wang, L.P., Basu, S., & Zhang, Z. M., (2011). Direct and indirect methods for calculating thermal emission from layered structures with nonuniform temperatures. Journal of Heat Transfer, 133(7), 072701–7.

Chan, D.L.C, Soljačić, M., & Joannopoulos, J. D. (2006). Direct calculation of thermal emission for three-dimensionally periodic photonic crystal slabs. Physical Review E, 74(3), 036615-9.

Shayegan, K. Biswas, S., Zhao, B., Fan, S., & Atwater, H. A. (2023). Direct observation of the violation of Kirchhoff’s law of thermal radiation. Nature Photonics, 17(10) 891–896.

Park, Y., Asadchy, V. S., Zhao, B., Guo, C., Wang, J., & Fan, S. (2021). Violating Kirchhoff’s Law of Thermal Radiation in Semitransparent Structures. ACS Photonics, 8(8), 2417–2424.

Shayegan, K. J., Hwang, J. S., Zhao, B., Raman, A. P., & Atwater, H. A. (2024). Broadband nonreciprocal thermal emissivity and absorptivity. Light: Science & Applications, 13(1), 176.

Zhang, Z., Dehaghi, A. K., Ghosh, P. & Zhu, L. (2025). Observation of Strong Nonreciprocal Thermal Emission. Physical Review Letters, 135(1), 016901.

Zhao, B. (2025). Radiation Imbalance: New Materials Emits Better Than It Absorbs. Physics, 18, 123.

Buchheit, T.E, Boyce, B. L., & Wellman, G. W. (2002). The role of microstructure in MEMS deformation and failure. In International Mechanical Engineering Congress & Exposition, 36428, 559–566.

Rahman, F., & Akanda, M. A. S. (2020). Numerical analysis of reaction forces at the supports of sliding microwire. Journal of Mechanical engineering4 and Sciences, 14(4), 7434–7445.

Fu, D., Levander, A. X., Zhang, R., Ager III, J. W., & Wu, J. (2011). Electrothermally driven current vortices in inhomogeneous bipolar semiconductors. Physical Review B., 84(4), 045205.

Rahman, F., & Akanda, M. A. S. (2023). Quantification of Electrostatic and Adhesive Forces Between Microwire and Microprobe Using Experimental and Numerical Approaches. Arabian Journal of Science and Engineering, 49(2), 1673-1682.