This paper presents a theoretical study of a Condition Monitoring Method (CMM) for three-phase induction machines within the framework of Industry 4.0. The proposed approach integrates electrical and mechanical indicators to enhance fault detection sensitivity and reliability in digitally connected industrial systems. Unlike conventional Machine Current Signature Analysis (MCSA), the CMM employs a model-based structure supported by adaptive learning, intelligent alarm logic, and built-in redundancy. These features enable the system to interpret complex signal patterns, distinguish transient disturbances from persistent faults, and avoid missed alarms caused by learning an already degraded state. The innovation of this work lies in the formulation of a unified theoretical framework that connects model-based residual analysis, adaptive statistical decision-making, and digital system integration. The study contributes to knowledge by defining how these elements can be architected within Industry 4.0 environments, enabling predictive maintenance strategies that are data-driven, interoperable, and self-adaptive. Although no experimental validation is presented, the conceptual framework establishes a foundation for the future development of intelligent diagnostic systems that combine physical modelling with digital analytics. In summary, this work provides a novel conceptual model that bridges traditional condition monitoring and modern cyber-physical production systems, contributing to the theoretical advancement of intelligent, Industry 4.0-compatible maintenance architectures.

The ongoing industrial transformation driven by Industry 4.0 has fundamentally reshaped the way condition monitoring (CM) and predictive maintenance (PdM) are conceived and implemented. Intelligent, connected, and adaptive systems now form the backbone of modern industrial operations, integrating digital twins, data analytics, and cyber-physical infrastructures to ensure reliability and operational efficiency. In line with the Tech Forum Journal’s scope—promoting innovation in intelligent engineering, digital systems, and industrial automation—this work contributes a novel theoretical foundation for condition monitoring of induction machines that directly supports the advancement of smart manufacturing systems.

This work advances the theoretical foundation of condition monitoring for induction machines by integrating model-based residual analysis, adaptive learning, and intelligent alarm systems. The proposed Condition Monitoring Method (CMM) framework introduces built-in redundancy, a statistical persistence mechanism, and a reference machine database that collectively enhance sensitivity and reliability. Unlike conventional Machine Current Signature Analysis (MCSA) approaches, this method formalises a digital-ready architecture consistent with Industry 4.0 principles, enabling real-time, interconnected, and self-adaptive diagnostic systems. Although theoretical in nature, the study contributes a novel conceptual model that defines how electrical and mechanical monitoring parameters can be combined to support predictive maintenance and fault prevention in smart industrial environments.

Condition monitoring of induction machines has evolved from classical signal-based analysis to hybrid intelligent frameworks that integrate modelling, learning, and digital connectivity. Early model-based diagnostic approaches [1, 2], established the theoretical basis for residual generation and analytical redundancy in fault detection. These studies demonstrated how dynamic models could be used to estimate normal operating behaviour, allowing deviations in system parameters to serve as indicators of faults. Although initially applied in aerospace systems, such principles are directly applicable to industrial electromechanical equipment.

Traditional MCSA remains one of the most widely used non-intrusive diagnostic techniques for rotating machinery. By analysing frequency components in the stator current spectrum, MCSA can detect electrical and mechanical irregularities such as broken rotor bars, eccentricity, or bearing faults. However, as Krause et al. [3] showed, purely spectral techniques are limited by noise, variable load conditions, and power-supply disturbances, which often result in misclassifications or undetected faults. According to Kumar [4], these limitations underline the need for complementary approaches that fuse electrical and mechanical observables to achieve more reliable diagnostic performance.

In response to these challenges, recent studies have explored hybrid approaches that integrate multi-domain sensing and data-driven analysis. Chitariu [6] proposed a method that combines electrical power monitoring with mechanical vibration indicators to detect asymmetries and eccentricities in induction machines. Similarly, Chinis & Stavroulakis [5] emphasised the importance of integrated, low-cost predictive maintenance solutions for small and medium-sized enterprises seeking to adopt Industry 4.0 technologies. These findings confirm that the next generation of CM systems must go beyond isolated signal analysis and embrace data fusion and adaptive intelligence.

With the increasing maturity of digital manufacturing, PdM frameworks have become heavily reliant on data analytics and machine learning. Hector and Panjanathan [7] demonstrated that intelligent algorithms, when combined with expert knowledge and physical models, significantly enhance fault-detection accuracy and generalisation under non-stationary conditions. Mallioris et al. [8] expanded this view by mapping predictive maintenance applications across industries, concluding that the most robust systems combine physics-informed modelling with adaptive data-driven learning to achieve both interpretability and scalability. The proposed CMM aligns with this trend by implementing a hybrid model-learning architecture that continuously adapts to operating conditions while maintaining a physically meaningful residual model.

The emergence of digital-twin (DT) technology has further transformed condition monitoring. Liu et al. [9] described DT-driven CM as an evolutionary step in which a virtual model of the machine mirrors the physical asset in real time, enabling residual-based diagnostics, virtual testing, and predictive decision-making. Chen et al. [10] identified sensor virtualisation, high-speed data streaming, and cloud-edge computing as the enabling technologies that make this integration feasible. Yin et al. [11] demonstrated a DT-driven system capable of detecting both electrical and mechanical faults by comparing simulated and measured current signals, showing the value of combining model-based and data-driven reasoning. In parallel, Diversi et al. [12] proposed an autoregressive-based MCSA method that improves spectral estimation accuracy and robustness against noise, illustrating the relevance of adaptive signal models for intelligent fault detection.

Despite these advancements, few studies have proposed a unified conceptual framework that merges model-based residual analysis, adaptive learning, persistence testing, and reference-state databases into a single architecture suitable for Industry 4.0 environments. The proposed CMM addresses this gap by integrating physical modelling, intelligent learning, and redundancy principles into one coherent structure.

It explicitly links electrical and mechanical indicators through adaptive residual modelling and employs built-in safeguards against false learning by referencing previously validated healthy states. In doing so, it contributes both theoretically and practically to the development of intelligent, self-adaptive maintenance systems that support data-driven decision-making within digital manufacturing ecosystems.

The comparison in Table 1 highlights that existing approaches are either model-based or data-driven, with few frameworks achieving an integrated, self-adaptive architecture suitable for Industry 4.0 environments. The proposed CMM seeks to bridge this gap by combining residual analysis, adaptive learning, and redundancy within a digital-ready monitoring framework.

| Author(s) and Year | Main Focus / Methodology | Application Domain | Key Strengths | Limitations | Contribution of Present Study (CMM) |

| Duyar et al. [1]; Eldem \& Duyar [2] | Model-based fault detection using residual generation and parameter estimation | Aerospace and actuation systems | Established analytical redundancy and model-based fault identification | Limited adaptability; not connected to digital or Industry 4.0 environments | Extends model-based residual concepts with adaptive learning, persistence logic, and integration into digital systems |

| Kumar [4] | Review of traditional condition monitoring methods such as MCSA, vibration, and thermal analysis | General induction motor systems | Comprehensive summary of conventional diagnostic techniques | Does not address integration with digital or learning-based methods | Builds upon reviewed limitations by proposing a hybrid digital-ready framework |

| Krause et al. [3] | Non-intrusive MCSA using spectral analysis of motor currents | Industrial rotating machinery | Accurate for electrical fault detection under stable conditions | Susceptible to noise and variable load conditions; limited to electrical domain | Enhances diagnostic reliability by fusing electrical and mechanical indicators |

| Chitariu [6] | Electrical power-based analysis for fault detection in three-phase asynchronous motors | Electrical machines and drives | Combines power signal analysis with physical insight | Lacks adaptive intelligence and digital integration | Incorporates model-based adaptation and fault-state protection for real-time diagnostics |

| Hector \& Panjanathan [7]; Mallioris et al. [8] | Machine learning and predictive maintenance strategies for Industry 4.0 | Cross-sector industrial systems | Demonstrate scalability and improved fault classification through AI | Depend heavily on large datasets and lack interpretability | Integrates learning into a physics-based model to retain interpretability and reduce data dependency |

| Liu et al. [9]; Chen et al. [10]; Yin et al. [11] | Digital twin frameworks for online condition monitoring and predictive maintenance | Cyber-physical industrial systems | Enable real-time synchronisation between virtual and physical assets | Require complex infrastructure and high data throughput | Provides a theoretical foundation for integrating residual-based learning within digital twin architectures |

| Diversi et al. [12] | Autoregressive-based MCSA for enhanced spectral estimation and noise robustness | Electrical drives and motor systems | Improved frequency resolution and noise tolerance | Focused on signal analysis without system-level redundancy | Embeds adaptive spectral modelling into a redundant diagnostic architecture |

| Chinis \& Stavroulakis [5] | Implementation of predictive maintenance for SMEs within Industry 4.0 | Small and medium-sized enterprises | Emphasises cost-effective adoption of PdM technologies | Limited discussion of hybrid or model-based approaches | Aligns with SME applicability through scalable, data-light architecture |

| Present Study (CMM) | Unified model-based residual analysis with adaptive learning, persistence logic, and reference-state redundancy | Induction machines in Industry 4.0 environments | Integrates physical modelling, statistical learning, and redundancy; digital twin-compatible; interpretable | Currently theoretical; requires experimental validation | Establishes a digital-ready theoretical framework for intelligent, self-adaptive condition monitoring |

By situating the CMM within a broader cyber-physical production framework, this study strengthens the connection between traditional condition monitoring, digital twins, and intelligent maintenance systems [10, 12]. The research embodies the interdisciplinary innovation at the core of the Tech Forum Journal’s mission, bridging mechanical engineering, information technology, and industrial automation. It provides a conceptual model for how next-generation predictive maintenance systems can merge physical modelling, statistical learning, and digital interoperability, laying the groundwork for resilient and intelligent maintenance architectures in Industry 4.0 applications.

Practically all mechanical movement that is carried out in an industrial plant originates from the rotor of a machine. They are the ones who put the assembly lines to work and give life to robotic arms and automation machines. Mechanical and electrical problems can cause the machine to fail and cause production line downtime. In this sense, it is essential to know the main causes of failure and know how to avoid them. There is no factory in the world that does not use electric machines extensively. They are responsible for setting factories in motion. Because it is such an important part in industries, it is essential to have a good prevention and maintenance program to prevent the most common failures. Problems can come from a variety of sources, most of which can be avoided with a good maintenance program and well-trained staff. Some of the most common failures in electric machines are:

Overload

Overloading happens when a machine is required beyond its rated torque. This situation causes the operating electric current to be higher than normal, causing overheating. With the machine running at a higher temperature, its useful life decreases and depending on the level of overload the protection device of the circuit that feeds the machine will be activated, giving rise to an unexpected stop in the operation of that machine.

Misalignment

Misalignment is a common cause of failures in electric machines. It happens when the machine drive shaft (rotor) or coupling part is not correctly aligned with the load. Misalignment results in the transfer of mechanical stresses that are harmful to the machine, increasing wear and apparent mechanical load. Another undesirable effect is the increase in vibration both in the applied load and in the machine itself.

Voltage Transients

Voltage transients are the voltage signals of transient characteristics that happen whenever a circuit or load is triggered. These transients are associated with large spikes in electromagnetic interference and, depending on their peak and frequency values, can cause damage to the devices connected in the circuit in which the transient happens. The big problem for machines is the breakage/loss of insulation in the machine winding. Since voltage transients have different causes and are not always a recurring phenomenon, it is difficult to find the cause. Without the insulation in good conditions, the machine is out of operation and implies the stoppage of the production line associated with it.

Harmonic Distortion

Harmonics are the high-frequency components of an electrical signal. The signal from the power grid in Brazil is 60Hz. However, in the presence of nonlinear loads, the voltage/current waveform can suffer distortions that are associated with the introduction of harmonics into the network, which are signals whose frequency is a multiple of the nominal frequency of the network. In the case of machines, harmonic distortion can be understood as an additional source of energy that circulates through the windings, generating additional energy losses (which happens in the form of heat generation). In addition to the increase in temperature, distortions also decrease machine efficiency.

Sigma Current

Sigma currents are the eddy currents that circulate through an electrical circuit. They are generated by capacitances and parasitic inductances associated with electrical conductors. These currents are associated with loss of efficiency and decreased service life. Its prevention involves the use of well-dimensioned and quality conductors, in addition to avoiding welds or inadequate connections of the conductor, which compromises the original ohmic characteristics of the cable.

Unbalanced Phases

The machines in operation in the industry are mostly of the induction type with squirrel cage. They are asynchronous machines powered by three-phase circuits. For the correct operation of the machine and generation of the rotating field, it is important that the three phases that feed the stator are balanced.

Unbalanced circuits can generate distortions in the electrical characteristics of the circuit and create stalling situations. In general, it also causes overheating and problems in the insulation of the machine windings.

Soft foot

This problem, the origin of failures in electric machines more common than one might think, concerns cases in which the fixing of the machine’s feet or its driven component are not seated on the same surface. This operating condition can cause new mechanical misalignment stresses to be introduced into the assembly when tightening the fixing screws of each foot.

The main impact of the soft foot is the misalignment of the machine and load shafts. To avoid the problem, it is necessary to affix both the machine and the load in such a way that the seating does not cause additional vibration or transfer of forces to the machine.

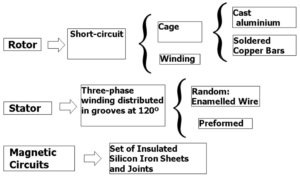

Its construction aspects are shown in Figure 1.

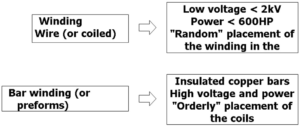

The constructive form of the Windings is shown in Figure 2.

The stator isolation in machines with bar windings has:

Insulating wall: thicker element that separates the coil assembly from the outside. It must be to withstand the voltage corresponding to the level of the machine.

Insulation between turns and elementary conductors: The turns formed individually to reduce losses. It is necessary that there is isolation between them and between the conductors that form them.

Protective straps and covers: protective straps and covers are used to protect those in the groove areas.

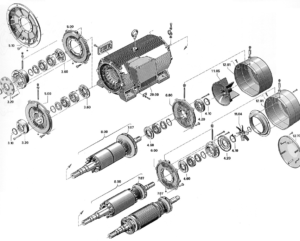

Disassembling a machine is a way to better understand its inside and parts, as shown in Figure 3.

The Working Principle of an induction machine is:

Three sinusoidal currents have the same amplitude and are 120º out of step with each other

Three coils of equal impedance are arranged 120º geometrically to each other

The sine currents circulating through the 3 coils produce a rotating magnetic field of constant intensity.

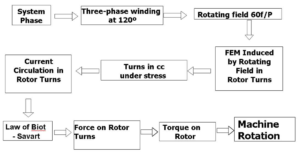

Leading to a sequence of electromagnetic effects, as shown in Figure 4.

And to the sequence of relations as shown in Figure 5.

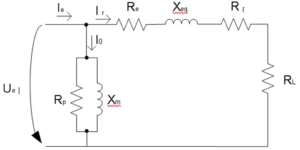

The Equivalent Circuit of Moving rotor is shown in Figure 6.

Several operating regimes can be distinguished: as a motor, as a generator and as a brake. Depending on the ratio of Ns and Nr speeds, one can have:

If s\(<\)0, then works as asynchronous generator.

If s=0, then the asynchronous machine is free load.

If 0 \(<\) s \(<\) 1, then works as asynchronous motor.

If s=1, then the asynchronous machine is at startup.

If s \(>\) 1, Nr \(<\) 0 (rotor rotates in the opposite direction to the rotating field), then works as a brake.

The power balance is shown in Figure 7

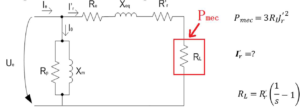

For the machine analysis, the total mechanical power is at focus. Figure 8. shows the mechanical power in the equivalent circuit and its equation.

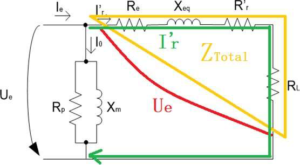

Serial impedance association \[Z_{Total}=\sqrt{\left(R_e+R_r^{\prime}+R_L\right)^2+\left(X_{eq}\right)^2}.\]

Widespread Ohm’s Law \[I_r^{\prime}=\frac{U_e}{Z_{Total}}.\]

Replacing \[I_r^{\prime}=\frac{U_e}{\sqrt{\left(R_e+R_r^{\prime}+R_L\right)^2+\left(X_{eq}\right)^2}}.\]

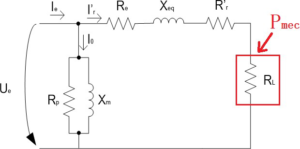

Total mechanical power of the machine is shown in Figure 10.

\[P_{mec}=3R_L I_r^{\prime\,2}.\]

\[I_r^{\prime}=\frac{U_e}{\sqrt{\left(R_e+R_r^{\prime}+R_L\right)^2+\left(X_{eq}\right)^2}}.\]

\[R_L=R_r^{\prime}\left(\frac{1}{s}-1\right).\]

Replacing \[P_{mec} =3\left[R_r^{\prime}\left(\frac{1}{s}-1\right)\right] \left( \frac{U_e}{\sqrt{\left(R_e+R_r^{\prime}+R_L\right)^2+\left(X_{eq}\right)^2}} \right)^2.\]

Total mechanical power of the machine \[P_{mec} =3\left[R_r^{\prime}\left(\frac{1}{s}-1\right)\right] \left( \frac{U_e}{\sqrt{\left(R_e+R_r^{\prime}+R_L\right)^2+\left(X_{eq}\right)^2}} \right)^2.\]

Simplifying \[P_{mec} =3R_r^{\prime}\left(\frac{1}{s}-1\right) \frac{U_e^{2}} {\left(R_e+R_r^{\prime}+R_r^{\prime}\left(\frac{1}{s}-1\right)\right)^2 +\left(X_{eq}\right)^2},\] or \[P_{mec} =3R_r^{\prime}s(1-s) \frac{U_e^{2}} {\left(sR_e+R_r^{\prime}\right)^2+s^{2}\left(X_{eq}\right)^2}.\]

CMM is a recent electric machine analysis technology, which works based on Artificial Intelligence that compares the real machine to be monitored, with a mathematical model of the machine, operating at different load conditions. This mathematical model is obtained from a learning period lasting a few days. The CMM diagnostic monitoring system is also designed to detect electrical faults in machines in response to the limitations of vibration monitoring. In addition to electrical failure modes, it also detects mechanical failure modes in the machine or driven machinery. It appears as the only alternative in situations where dedicated vibration monitoring is not practical, economical or comprehensive enough. It can detect changes in the load that the machine is facing due to anomalies in the equipment or driven process, such as cavitation or clogged filters and screens. The CMM is installed in the power supply frame of the machine and thus, as it does not require the installation of a sensor in the machine itself or in the driven machine, unlike when using a vibration analyzer, it is especially suitable for inaccessible driven equipment or in hazardous areas and is applicable to most types of pumps, compressors and similar machines. It is also suitable for monitoring submersible, wellbore, downhole and encapsulated pumps.

The parameters to measure and observe are:

Temperature monitoring

Vibration monitoring

Voltage monitoring

Pressure monitoring

Rotational speed monitoring

Force monitoring

And the flaults that can be detect are:

Bearing failures

Overheating

Shaft unbalance

Clearance mounting

Gear tooth failure

Load misalignment

Stator eccentricity

Other catastrophic machine failures

To perform the analysis of electric machines, the CMM monitor uses a combination of dynamic voltage and current waveforms, along with learned models, to detect faults in the machine or driven equipment. The monitor detects differences between the current observed characteristics and the learned characteristics and relates these differences to failures. The operating principle of the CMM monitor is based on the elaboration of a mathematical model of the electric machine and the observation of deviations from this model. The detection of electric machine failures is based on a machine model, learned by the monitor, based on physics, in which the constants in the model are calculated from real-time data and compared to previously learned values. Mechanical fault detection is based on the power spectral density (PSD) amplitudes in specific frequency bands, relative to the learned values. This information is automatically combined with diagnostic expertise. Because of this spectral band approach, mechanical flaw detection provides guidance for a class of potential flaws. The sensitivity to some failures (e.g. rolling element bearing failures) will decrease with distance from the component in the process of failure. On the other hand, faults that increase machine load are independent of the distance from the machine.

For modelling and fault detection, the CMM uses four different approaches to fault detection and analysis:

based on the internal characteristics of the electric machine

based on frequency analysis of the residual current spectrum

analyses the actual voltages and currents of the electric machine supply to check for certain types of faults in the mains supply and current

uses data from a database of similar electric machines to provide an independent diagnostic reference.

For an ideal electric machine, the voltage and current waveforms are sinusoidal. The change in the mains voltage creates magnetic forces that cause the rotor to rotate, and the amplitude and phase of the machine currents are related to the input voltages through the internal mechanical and electrical operation of the machine. The internal electrical and mechanical parts of the electric machine can be thought of as a transfer function that converts the waveform of the input voltage into the waveform of the output current.

The monitor uses a linear model for the internal electrical and mechanical parts of the electric machine. This physics-based model is derived from a set of differential equations and can be expressed as a transfer function. During the learning process, the monitor determines the coefficients of this model. For a normal electric machine, the model transfer function is a great approximation to the actual physical transfer function of the machine.

During monitoring, the CMM monitor measures the input voltage waveform and passes it through the model’s transfer function to obtain a theoretical current waveform. Meanwhile, the actual transfer function of the machine converts the waveform of the input voltage into the observed current waveform (measured). The theoretical current waveform is subtracted from the measured current waveform to produce a residual current waveform. The residual waveform contains the deviations between theory and reality, and the monitor uses this residual waveform for mechanical failure analysis. Changes in the internal characteristics of the electric machine (e.g., a short-circuited winding) will cause the actual transfer function of the electric machine to be altered. During monitoring, the CMM unit obtains the measured waveforms of voltage and current and calculates a new set of observed coefficients for the internal model of the machine. The coefficients of the original model are subtracted from the observed coefficients to produce residuals. These residues are used to detect internal problems of the electric machine.

In an ideal electric machine, the rotor would be perfectly centered in the stator gap, rotate smoothly and is balanced. In real machines, the rotor is never perfectly centered on the stator, the bearings and the driven equipment create forces and vibrations, and the rotor always has some imbalance. Mechanical breakdowns disturb the position of the rotor and create disturbances and distortions in the actual waveforms. As faults develop in the machine assembly, they cause the actual output current to deviate even further from the theoretical.

A failure in a bearing will cause a periodic disturbance in the position of the rotor; This disturbance in the position of the rotor will create a corresponding disturbance in the clearance of the air gap and modulation of the amplitude of the machine current. Modulation produces sidebands around the grid frequency in the residual current spectrum and the distance of the sidebands from the grid frequency will match the frequency of the bearing defect.

Other types of faults can produce a wide variety of additional frequency content in the actual waveforms. CMM processing looks for this additional frequency content and uses it to diagnose different classes of mechanical problems.

The CMM monitor reports categories of faults that act as indications and point to areas that should be investigated further. It uses four independent fault detection methods that cover two categories: electrical and mechanical.

Electrical breakdowns are associated with internal machine problems or external power problems. The CMM unit monitors both using two independent methods. Internal machine faults are detected using the learned internal model of the machine as a reference. During each monitoring iteration, the monitor calculates a set of eight internal machine model parameters based on the observed voltage and current. These observed parameters are compared with the parameters obtained during the learning phase and significant and persistent changes are detected and reported as electrical faults. These failures include the following examples:

Loose windings

Stator Problem

Short circuit

The external power supply is directly checked for voltage or current unbalance, voltage range, maximum current, and low voltage or current.

Categories of mechanical failures are detected and diagnosed using the PSD spectrum of the residual current waveform. The residual current represents the difference between the observed current and the theoretical current produced by the internal model of the machine using the same observed voltage. The PSD spectrum is divided into twelve frequency bands that are usually associated with certain mechanical problems (listed below). Analysis of these frequency bands yields classes of failures for further investigation.

Lose Foundation/Components

Unbalance/Misalignment/Coupling/Bearing

Belt / Drive Element / Driven Equipment

Bearing

Rotor

The machine database provides an independent analysis if the CMM unit learns a faulty system. The machine database consists of normal and high values for each of the twelve PSD spectrum bands based on experience with many similar machines. If a residual value of the PSD spectrum range exceeds the High value of the database, after the persistence check, the monitor will warn you that something is wrong.

CMM is a powerful electric machine monitoring system. However, there are some limitations in its use and interpretation:

It cannot be used for DC or single-phase machines

For variable frequency drives, the cut-off frequency of the drive should be higher than a few kHz

The CMM unit cannot be used on machines with rapidly varying voltage or power. The load/speed cannot always vary very quickly due to the need for learning time, for each load condition.

Mechanical diagnostics are energy-based in twelve spectral frequency ranges. This is, by nature, a rough analysis and diagnostic indications usually represent only broad classes of problems. As is normal in permanent monitoring systems, the user will need to implement additional inspections to confirm and determine the actual failure.

The CMM cannot be used on machines with rapidly varying voltage or power. This is not a serious restriction for most applications, but some applications, such as shredders, do not meet this requirement. If a sudden change in load occurs, the monitor will reject that sample; However, the same machine could constantly run with some load, and this would allow the unit to monitor the machine.

The CMM unit works very well in applications where the machine is located some distance from the current or potential transformers. However, the power supply at the measuring point used must be dedicated to a single machine. On the other hand, a set of power stations can be used for all machines that are supplied from the same voltage source. The current measurement constraint is a consideration for subsea applications where power can be supplied to the seabed only to branch out to multiple machines. In this case, a CMM unit cannot be used for the main power. However, it could be used if current transformers could be installed in each branch.

Although this study does not include experimental validation, it provides original theoretical results by formalising a Condition Monitoring Method (CMM) that extends beyond conventional Machine Current Signature Analysis (MCSA). The proposed framework introduces several innovations:

1. Unified theoretical model – The paper establishes a conceptual model that jointly interprets electrical and mechanical indicators through model-based residual analysis, enabling a holistic understanding of induction-machine behaviour under fault conditions.

2. Intelligent diagnostic architecture – It formulates an alarm logic that combines statistical analysis with an adaptive persistence test, creating a self-adjusting mechanism capable of differentiating transient events from persistent faults.

3. Adaptive learning with fault-state protection – The framework defines a database of reference machine states that prevents the system from mis-learning an already faulty condition — a feature rarely described in prior literature.

4. Redundant and robust design principles – Built-in redundancy across multiple diagnostic pathways is proposed to enhance reliability and maintain diagnostic performance even with partial signal loss or sensor degradation.

5. Integration with Industry 4.0 paradigms – The model explicitly connects condition monitoring to cyber-physical and data-driven production systems, defining how CMM can operate as part of digital maintenance architectures.

These contributions collectively represent the main original results of this theoretical study. They provide a foundation for implementing and experimentally validating intelligent, model-based predictive-maintenance systems in future work.

This study presented a theoretical approach to the condition control of three-phase induction machines within the framework of Industry 4.0, emphasising the combined use of electrical and mechanical indicators for early fault detection. The proposed Condition Monitoring Method (CMM) employs model-based residual analysis and frequency-domain interpretation to identify deviations in machine behaviour that precede critical failures.

CMM is a powerful system for monitoring and analysing electric machines. Its effectiveness arises from sophisticated signal-processing and diagnostic algorithms, reinforced by built-in redundancy that enhances robustness. The method’s adaptive learning capability provides both sensitivity and flexibility, while its database of reference machine states prevents missed alarms caused by learning an already faulty condition. The alarm logic integrates statistical analysis with an adaptive persistence test, enabling the system to distinguish between transient anomalies and persistent faults. Together, these features represent a significant improvement over conventional Machine Current Signature Analysis (MCSA) and are consistent with results reported in numerous industrial case studies.

The principal innovation of this work lies in the formulation of a unified theoretical framework that integrates model-based monitoring, adaptive statistical decision-making, and intelligent alarm management within an Industry 4.0 context. The study contributes to knowledge by defining a conceptual architecture that combines physical modelling with digital analytics, demonstrating how redundancy, adaptive learning, and data connectivity can be embedded into predictive maintenance systems. This synthesis bridges traditional condition monitoring with cyber-physical production systems, providing a new theoretical basis for the development of intelligent, self-adaptive maintenance solutions.

Looking ahead, the integration of model-based CMM with machine learning and cloud-edge analytics will further enhance adaptability, accuracy, and scalability. Future research will focus on validating the proposed framework under diverse operating conditions and quantifying its diagnostic performance, computational efficiency, and long-term stability.

In summary, the CMM provides a robust theoretical foundation for predictive maintenance of induction machines in Industry 4.0 applications—combining engineering rigour, data-driven intelligence, and digital interoperability to enable more efficient and resilient electromechanical systems.

Duyar, A., Merrill, W., & Guo, T.-H. (1991). A distributed fault-detection and diagnosis system using on-line parameter estimation (NASA Technical Report No. 19910016382). NASA Technical Reports Server (NTRS).

Eldem, V., & Duyar, A. (1993). Parametrization of multivariable systems using output injections: alpha canonical forms. Automatica, 29(4), 1127-1131.

Krause, T. C., Huchel, Ł., Green, D. H., Lee, K., & Leeb, S. B. (2023). Nonintrusive motor current signature analysis. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement, 72, 9000213.

Kumar, D. (2019). A brief review of condition monitoring techniques for the induction motor. Canadian Journal of Electrical and Computer Engineering, 42(1), 35–44.

Chinis, D., & Stavroulakis, G. E. (2023). Band gap analysis for materials with cookie-shaped auxetic microstructures, using finite elements. Applied Sciences, 13(5), 2774.

Chitariu, D. F., Horodinca, M., Mihai, C. G., Bumbu, N. E., Dumitras, C. G., Seghedin, N. E., & Edutanu, F. D. (2024). Condition Monitoring of a Three-Phase AC Asynchronous Motor Based on the Analysis of the Instantaneous Active Electrical Power in No-Load Tests. Applied Sciences, 14(14), 6124.

Hector, I., & Panjanathan, R. (2024). Predictive maintenance in Industry 4.0: A survey of planning models and machine learning techniques. Peerj Computer Science, 10, e2016.

Mallioris, P., Aivazidou, E., & Bechtsis, D. (2024). Predictive maintenance in Industry 4.0: A systematic multi-sector mapping. CIRP Journal of Manufacturing Science and Technology, 50, 80–103.

Liu, H., Zhang, Y., & Wang, C. (2022). Digital twin-driven condition monitoring: A review and framework. Smart Manufacturing Journal, 8(2), 45–60.

Chen, E., Yadav, V., & Agarwal, V. (2024). Digital Twin Enabling Technologies for Online Condition Monitoring of Nuclear Power Plant Components (No. INL/CON-24-76340-Rev000). Idaho National Laboratory (INL), Idaho Falls, ID (United States).

Yin, W., Hu, Y., Ding, G., & Chen, X. (2025). Digital Twin-Driven Condition Monitoring System for Traditional Complex Machinery in Service. Machines, 13(6), 464.

Diversi, R., Lenzi, A., Speciale, N., & Barbieri, M. (2025). An Autoregressive-Based Motor Current Signature Analysis Approach for Fault Diagnosis of Electric Motor-Driven Mechanisms. Sensors, 25(4), 1130.